Writing - The Mind of a Writer

"Sometimes I Feel Like a Crazy Man"

During this first month (June 2021) of my 4 Topics Plus newsletters, I’m laying some introductory groundwork here. For the next few weeks, it’s mostly all about me, me, me, as I share my background and qualifications for discussing one of four main topics - Writing, Art, Music, and Faith. Today we’re starting off with the topic of Writing. And, so it begins …

I never watched much of The Waltons on TV while growing up, but my two favorite things about that family were Mary Ellen’s eyebrows and the following dialogue from her older brother, John-Boy:

You know what’s in that writing tablet, Mama? All my secret thoughts. How I feel, and what I think about … You know, Mama, sometimes I hike on over to the highway, and I just sit and watch the buses go by, and the people in ‘em, and I’m wondering what they’re like, and what they say to each other, and where they’re bound for. Things stay in my mind, Mama. I can’t forget anything. And it all gets bottled up here in my head. And sometimes I feel like a crazy man! I can’t rest, or sleep, or anything, ‘til I rush off and write it down in that tablet.

John-Boy Walton, The Homecoming: A Christmas Story, 1971

Those words first grabbed my full attention nearly half a century ago, branding themselves upon my psyche. Behind the fictional John-Boy was an author or scriptwriter who felt like mentally-agitated kinfolk to me. Not that anyone, not even myself, would have guessed I had any writing ability at that barely-a-teenager point in my life. Aside from one-off magazine parodies I would sometimes compose and illustrate for my own entertainment, any outward sign of writing talent back then was buried, wholly latent.

Even so, I could relate to the crazy man writer inside of John-Boy Walton. I knew what it meant to be constantly overwhelmed with observations, thoughts, feelings, ideas, and sensations, all screaming to be organized into understandable streams of smooth-flowing words. Ink may not always flow from my pen to paper; my keyboard may not always be tapped into a digital file, but my writer's mind is always one that naturally organizes all these thoughts into words, words into sentences, sentences into paragraphs and chapters, and even whole volumes, with series and sequels.

My first semi-serious attempts at writing however were not born of such mental agitations or exercise. Around age five, I wrote and illustrated a presidential biography called, A Man Named Lincoln. It was largely plagiarized from a 1960 book with the same title, by Gertrude Norman and Joseph Cellini. Fortunately, they and their publisher never took any legal action against me.

Becoming a published poet prodigy a short time later similarly involved no crazy man struggles. I’m sure it took very little encouragement from a parent or teacher before I quickly composed the following verse:

I have a little turtle

His name is Pink

He likes to play with children

And he swims around the sink

This example of near-genius was printed with a byline in some school-district-wide mimeographed newsletter, bringing me praises from at least three respectable grown-ups I knew. With this publication, I essentially became the Poet Laureate (and teacher’s pet) of Mrs. Harford’s first grade class. But any such accolades left me with a hollow feeling inside. I had written an effortless piece of baloney.

I never had a pet turtle while in first grade. When I finally did get one several years later, it only confirmed what I knew all along — turtles might swim in sinks but, except for banana slugs, they are the unlikeliest of creatures to play with children. And the most painful self-confession of all? Never, ever, in real life would I have called a turtle “Pink” — or any other name solely intended to rhyme with a plumbing fixture. With these first inklings of self-critical cynicism surfacing in my life, I let writing go for another eight years, burying my nose in books by other writers instead.

Thanks to a challenging creative writing assignment in a ninth-grade English class, dormant enthusiasm for my own written words began to awaken inside me. Citing my paper as exemplary, Mrs. Locklear read my fictional tale of a surprise tiger attack out loud to riveted classmates. The story’s tension could be felt throughout the room and several exclamations of “wow” at the end indicated I might have some aptitude as a wordsmith.

There was no self-condemning cynicism this time around. I had worked hard on my paper, taking cues from the works of Roald Dahl, master of short stories with wickedly twisted endings.1 From then on, I put extra effort into my writing assignments - both fiction and non-fiction - and even got to write some flowery copy for our school’s yearbook. I minored in Historical Writing during my college years which trained me to thoroughly research and notate firsthand source documents. This fact-finding discipline honed my desire to only write or say things that could be verified, making me a terrible potential candidate for public office these days.

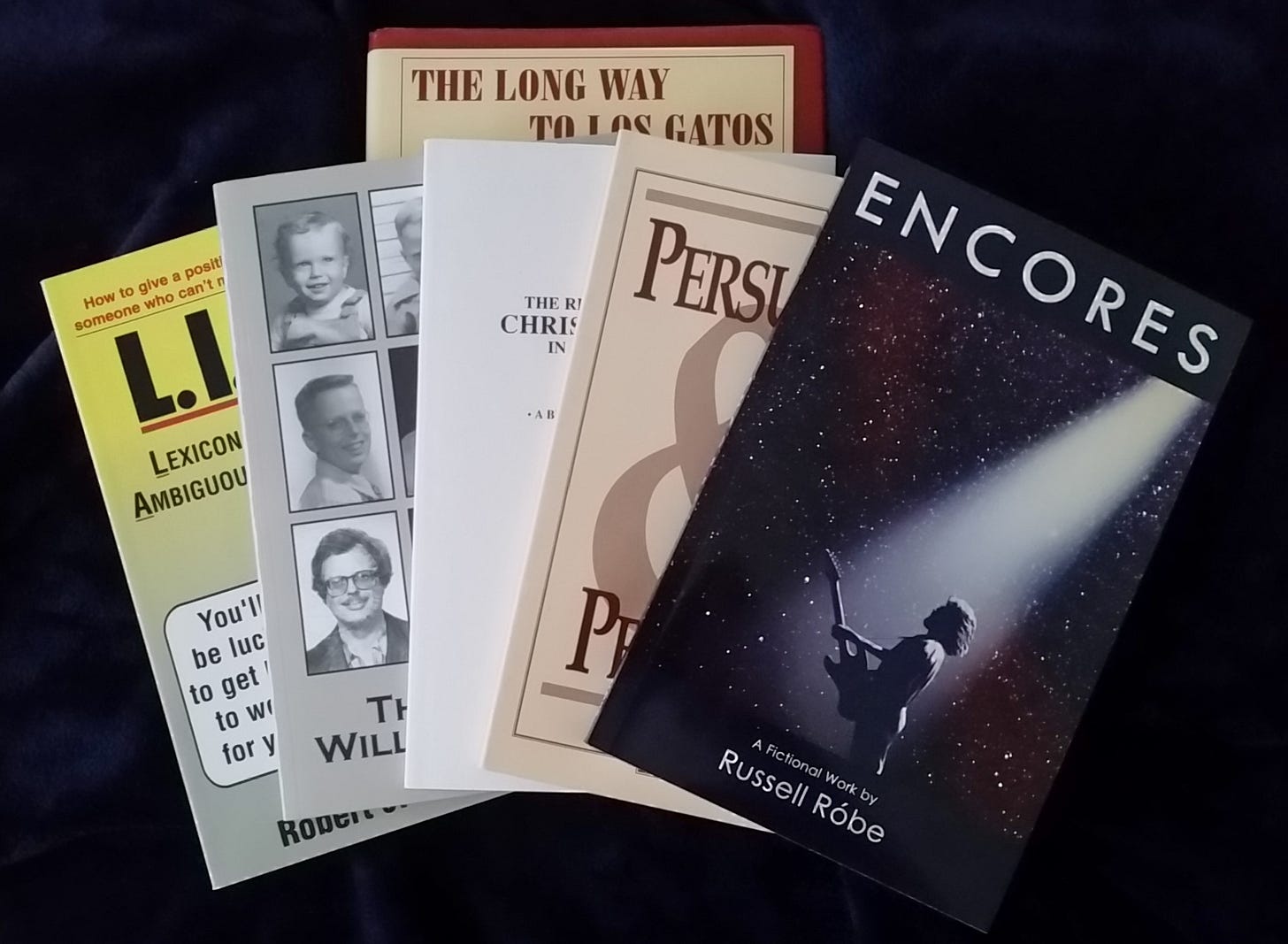

Not long after college graduation, I was greatly blessed with my first “real” job at a book manufacturing company, Publishers Press. Manuscripts from established publishers, and many first-time self-publishing authors, would cross my desk nearly every day. My job was to get their words and pictures organized into packages that co-workers could accompany through the various processes of creating finished books.

Not only did I get to read and absorb all these books’ different topics, but I learned (just before the digital era) how books were planned for printing and publication. I knew all the humorous insider’s lingo of the trade and, with a certain elbow-nudging superiority, could chuckle with my colleagues about “strippers, bleeding in the gutter.” I became proficient in copyright laws, fonts, text formatting and typesetting, graphics, half-tone illustrations, inks, paper thickness and color, folded signatures, trim sizes, cover materials and binding methods. I also had a front row seat to many of these books’ successes and failures, and saw how these resulted from good or bad choices of writing styles, content formatting, and marketing plans.

Most importantly perhaps, we worked next door to a highly respected publishing house and I was able to meet with their chief editor, Mr. Bickerstaff. Tall, slender, white-haired with good posture, he was a dignified, scholarly, British gentleman. I’m certain that he, like my British grandfather, wore a tie to the dinner table every evening. Mr. Bickerstaff sensed that I might like to occupy his desk upon his retirement and had me take a written test to judge my abilities as an editor. I thought I had done pretty well, but he politely summarized my shortcomings on the test by saying, “For this kind of job, you really have to love words.” I understood the underlying point of his message - I was still just a writer/editor wannabe at that moment in time.

Since then, the working of words - their meaning, their order, and their effect, has increasingly driven the way my brain functions. I’m constantly mulling the words of those who influence literature, marketing, politics, society, and my life. I have come to appreciate the beautiful writings of some authors who seemingly paint their words with an artist’s brush. I have been paying ever-keener attention to how my own written words may or may not be understood and enjoyed by others. Like Mark Twain, I now delight in finding just “the right word”2 for a sentence, with perfect satisfaction that any other word simply will not do. And while I still could not worthily occupy the late Mr. Bickerstaff’s venerable desk, he would appreciate, over thirty years later, that I really have come to love words.

This love has since resulted in a number of published magazine and newspaper articles. There have been a number of unpublished essays and short stories shared with family and friends. I have also written and produced some books of my own, and have provided editing and publishing assistance services for many writer friends and associates.

The collective success of these efforts has been relatively modest so far, never allowing me to “quit my day job” (of which there have been a variety since the Publishers Press days). But, to commemorate a recent milestone birthday, I came up with the following personal motto: “Everything up until now has just been practice!” Me and my crazy man’s writer mind are just getting started. My best books, articles, essays (and posts like these), have yet to be written!

Interestingly, Roald Dahl was married to Patricia Neal, who so wonderfully portrayed Mama in John-Boy’s “crazy man” confession scene.

“The difference between the almost right word and the right word is a large matter – it’s the difference between the lightning-bug and the lightning.” – Mark Twain